Markets Germany Magazine 3/24 | Heating Technologies

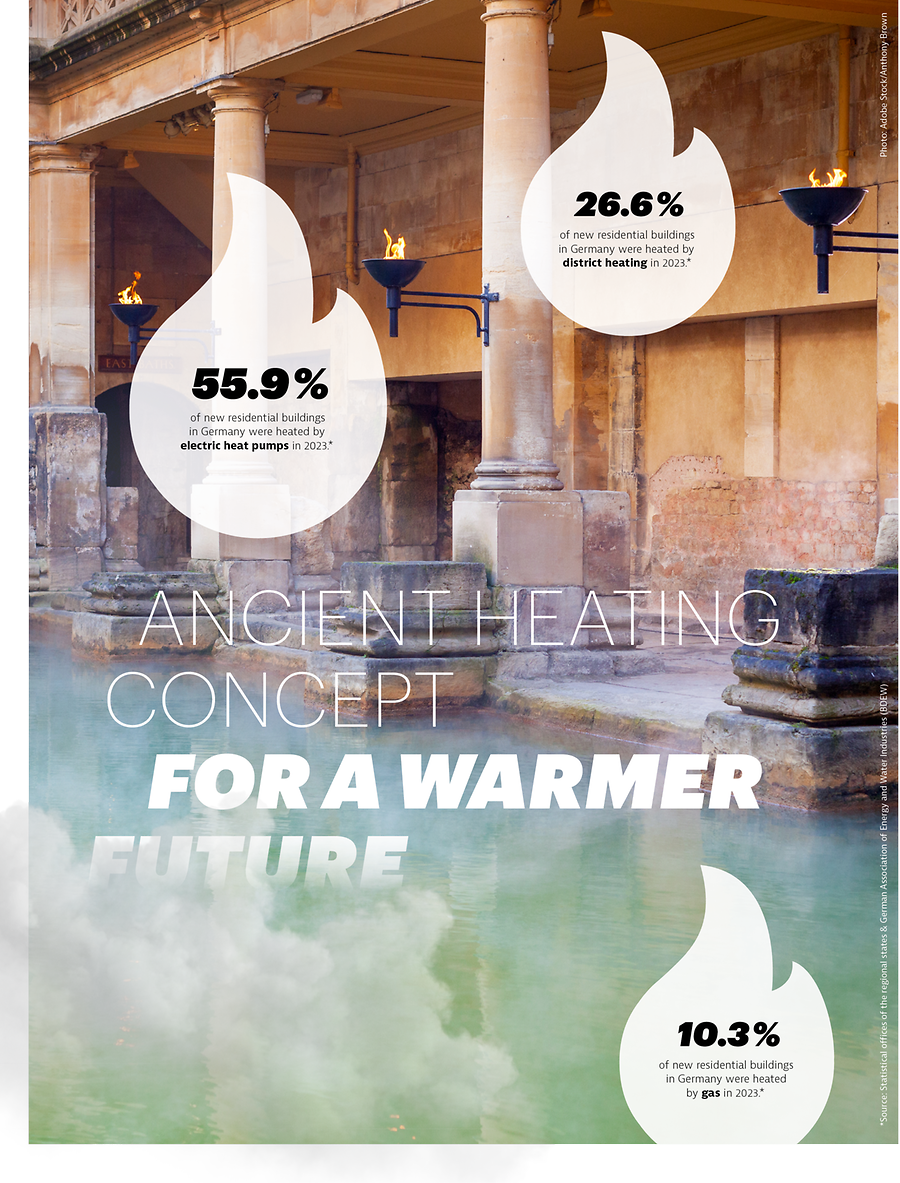

Ancient Heating Concept for a Warmer Future

If Germany is to meet its decarbonization goals, the country is going to have to change the way it heats residential and commercial buildings. So it’s looking to expand municipal heating—an idea that goes all the way back to antiquity.

Nov 19, 2024

Ancient Romans immersed in hot water and idly exchanging gossip with their peers may not have stopped to consider the intricate system enabling their daily sojourn to the public baths. Like the urbanite of today who hops into the shower without a second thought, hot water was something that simply appeared; the mechanisms underlying it were only interesting when they failed. But for historians of engineering, the baths of ancient Rome are held up in reverence as an early example of district heating. Powered by a wood-burning furnace, a boiler would heat the water before it travelled through pipes to the pools. The fumes produced in the process were cleverly redirected via a structure known as a hypocaust to heat the surrounding air.

Centuries later, modernized but analogous systems are attracting the interest of policymakers in Germany. Against the backdrop of the climate crisis, the transformation of heating systems has generated less public debate than sectors like transport and manufacturing have. But in much of the industrialized world, including in Germany, heating and cooling buildings accounts for more than a quarter of total energy consumption. And the heating industry is still dominated by fossil fuels, putting efforts to clean it up at the heart of the government’s climate policy.

This article was published in issue 3-2024 of the Markets Germany Magazine. Read more articles of this issue here

“It’s the elephant in the room,” says Robert Compton, an energy expert at Germany Trade & Invest, the government’s agency for international business promotion. “Heating is the biggest CO2 problem we face.”

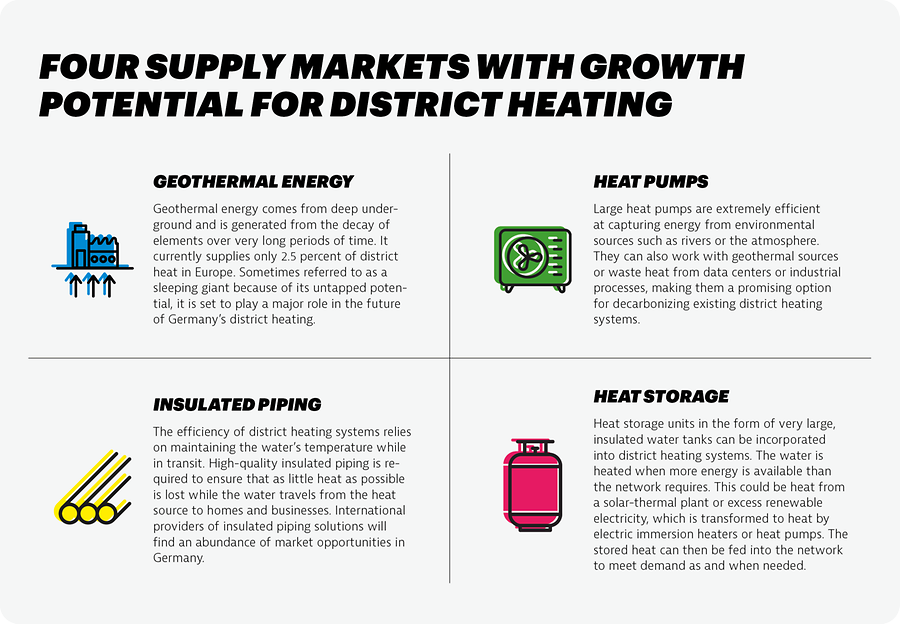

District heating systems (Fernwärme in German) have attracted particular attention because of their three main environmental advantages. By supplying buildings directly through a network of insulated pipes, they remove the need for individual boilers or central heating systems. To date they have tended to be served by power stations that generate both electricity and heat, a highly efficient process known as cogeneration. Finally, and most importantly, they can be flexibly powered by a combination of renewables such as geothermal, solar and biomass, or by large-scale heat pumps or waste heat sources, for example, by data centers. The main downside at present is that they require a large investment in infrastructure.

A state helping hand

The German government is addressing that challenge with the BEW (Bundesförderung für effiziente Wärmenetze) program, which offers financial support for creating new, renewable-powered district heating systems as well decarbonizing existing ones. The intention is to help municipal authorities make their heating sectors climate neutral by 2045 at the latest, a commitment that has been enshrined in German law since January of this year.

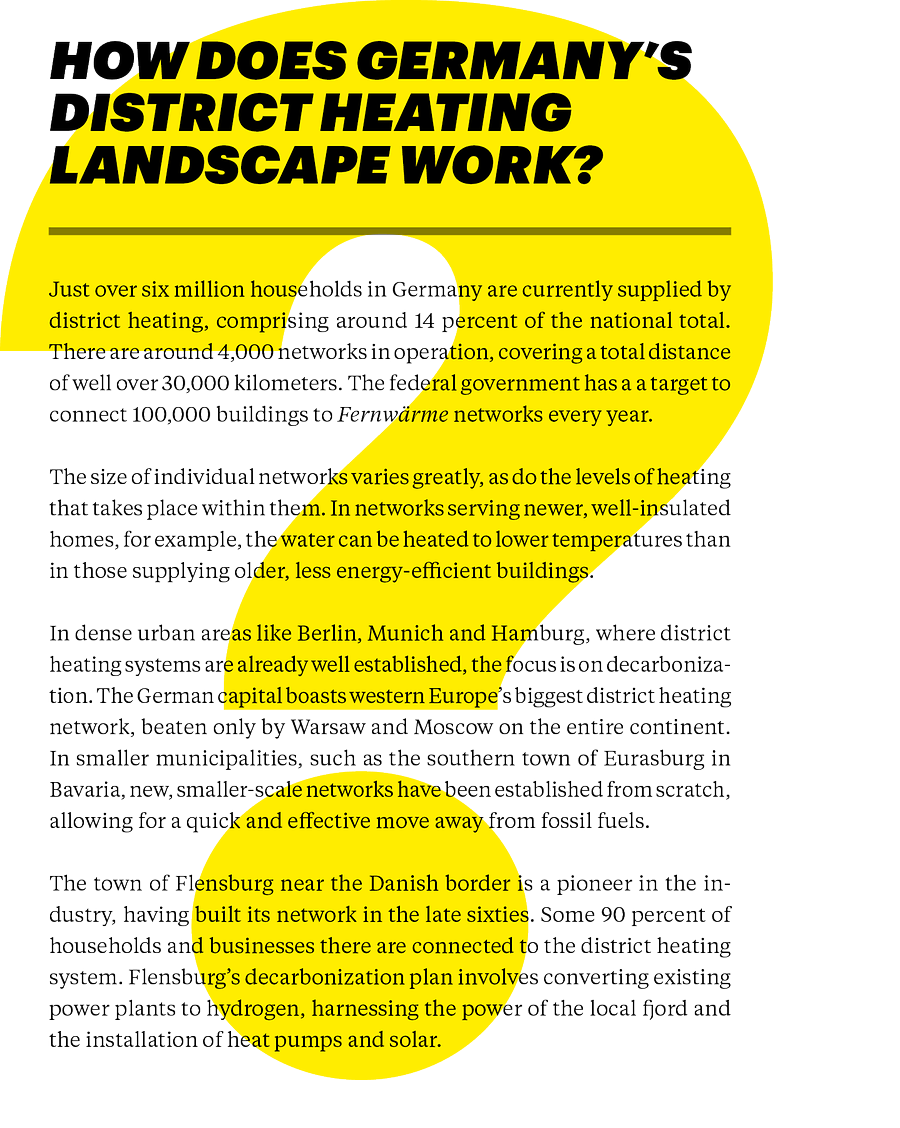

This is an ambitious undertaking, especially for smaller municipalities. Fossil fuels still account for over 80 percent of heat consumption in Germany, with natural gas dominating the sector. Some 14 percent of households are currently supplied via district heating networks, with less than a fifth of those powered exclusively by renewables. For companies operating in the sector, the German market therefore presents an abundance of opportunities.

The Bottom Line

Germany is investing heavily to make heating sustainable. With an ambitious plan to roll out district heating systems run on renewables, demand for heat pumps, insulated piping, geothermal energy and waste heat is set to soar.

“We expect to see a sharp increase in the portion of homes supplied with district heating from around a quarter to a third,” says Anna Kraus, a project officer for buildings and heat grids at Agora Energiewende, a think tank specializing in Germany’s transition to renewables.

Danish engineering company Danfoss has been developing district heating systems in Germany for several decades. It offers advice on early-phase planning, managing physical infrastructure and using software to monitor the network’s operations. One of the company’s recent projects was in Eurasburg, a municipality with a population of around 4,500 in southern Germany. Tasked with helping authorities to lower their carbon footprint, Danfoss installed a small district heating system serving 80 buildings including the local primary school, town hall and fire station. By eliminating the need for oil boilers, the initiative resulted in a 90 percent reduction in the community’s CO2 emissions.

The Eurasburg project could provide a blueprint for other small or medium-sized German municipalities now tasked with developing environmentally friendly heating plans for their communities. “We see a big development in Germany, where a lot of these smaller towns will have to decarbonize,” says Jonas Loholm Hamann, head of business development at the company’s district energy division.

Replacing and reconfiguring

As well as installing new heating systems, there are several opportunities to decarbonize existing ones. One way is to alter the heat source, replacing gas with renewables such as geothermal and solar or installing low-carbon technology like heat pumps. Tailoring systems to the individual needs of buildings is another powerful tool. Well-insulated, modern residential units, for example, do not need to be supplied with the same high temperature water as old, energy-inefficient buildings that are typically gas powered.

“We expect to see a sharp increase in the proportion of homes supplied with district heating.”

Anna Kraus, Agora Energiewende

In Berlin, municipal authorities recently took over the task of decarbonization after acquiring the city’s heating business from Swedish energy provider Vattenfall. The vast infrastructure, comprising a network of some 2,000 kilometers, includes Germany’s largest heat storage unit, located on the site of the Reuter West power plant. It can hold up to 56 million liters of water, warmed by surplus renewable energy, mainly from wind and solar plants. The storage unit can be flexibly connected to other sources, allowing it to be fed waste heat from processes such as sewerage treatment. Following a similar principle, in Hamburg, waste heat from a local metal factory is fed into the city’s district heating system.

The current boom in artificial intelligence, which requires enormous computing power that generates immense waste heat, could lead to further opportunities. The city of Frankfurt, which is a hub for data centers, is attracting a lot of attention in this regard. “Germany is already one of the most important markets for us, but we also see a big potential in the future,” says Loholm Hamann from Danfoss.

A blueprint for district heating

A sixty-year-old model for Fernwärme can be found in the northern German town of Flensburg, near the Danish border. Authorities there began installing district heating in the 1960s and have been in expansion mode ever since: today, more than 90 percent of households and businesses get their heat that way. For consumers, connecting to the system is a frictionless process. “They don’t have to invest in new heating facilities in order to be carbon neutral,” says Peer Holdensen, spokesperson for Flensburg’s public utility company. “Instead, they can rely on municipal authorities.”

Flensburg’s biggest challenge now is to decarbonize. The town has one coal-fired boiler still in operation, as well as two plants that run on natural gas that will be converted to hydrogen. Authorities are planning to build a large heat pump that will draw heat from the water in the Flensburg fjord, alongside solar thermal energy concepts and additional decentralized heat pumps that are also in development. The goal is to make Flensburg’s heating system carbon neutral by 2035, ten years ahead of the date mandated by the federal government. The project will require an investment of EUR 400 million, with grants from the BEW forming a cornerstone of the financing model.

Flensburg was an early adopter in an industry that has gained fresh relevance because of the imperative to decarbonize in the face of global warming and the climate crisis. According to Euroheat & Power, an international network promoting sustainable heating, Germany recorded the biggest expansion in district heat distribution networks within Europe in 2022. If all goes to plan, a further 100,000 German homes each year will be connected to district heating systems powered by clean energy. Achieving this goal will require joined-up thinking and collaboration between many players, from energy providers and software developers to building owners, municipal heating providers, utilities companies, as well as the manufacturers of heat pumps and insulated piping.

“This is very much a complex, multi-player operation,” says Compton from Germany Trade & Invest. It may sound like an epic task. But as the saying goes, Rome wasn’t built in a day.

Bath’s 2,000-year-old Roman baths are a UNESCO World Heritage site. District heating works on a similar principle, where heated water is piped to multiple dwellings.